FastRender: a browser built by thousands of parallel agents

In this newsletter:

Wilson Lin on FastRender: a browser built by thousands of parallel agents

Plus 13 links and 4 quotations and 2 TILs

If you find this newsletter useful, please consider sponsoring me via GitHub. $10/month and higher sponsors get a monthly newsletter with my summary of the most important trends of the past 30 days - here are previews from August and September.

Wilson Lin on FastRender: a browser built by thousands of parallel agents - 2026-01-23

Last week Cursor published Scaling long-running autonomous coding, an article describing their research efforts into coordinating large numbers of autonomous coding agents. One of the projects mentioned in the article was FastRender, a web browser they built from scratch using their agent swarms. I wanted to learn more so I asked Wilson Lin, the engineer behind FastRender, if we could record a conversation about the project. That 47 minute video is now available on YouTube. I’ve included some of the highlights below.

What FastRender can do right now

We started the conversation with a demo of FastRender loading different pages (03:15). The JavaScript engine isn’t working yet so we instead loaded github.com/wilsonzlin/fastrender, Wikipedia and CNN - all of which were usable, if a little slow to display.

JavaScript had been disabled by one of the agents, which decided to add a feature flag! 04:02

JavaScript is disabled right now. The agents made a decision as they were currently still implementing the engine and making progress towards other parts... they decided to turn it off or put it behind a feature flag, technically.

From side-project to core research

Wilson started what become FastRender as a personal side-project to explore the capabilities of the latest generation of frontier models - Claude Opus 4.5, GPT-5.1, and GPT-5.2. 00:56

FastRender was a personal project of mine from, I’d say, November. It was an experiment to see how well frontier models like Opus 4.5 and back then GPT-5.1 could do with much more complex, difficult tasks.

A browser rendering engine was the ideal choice for this, because it’s both extremely ambitious and complex but also well specified. And you can visually see how well it’s working! 01:57

As that experiment progressed, I was seeing better and better results from single agents that were able to actually make good progress on this project. And at that point, I wanted to see, well, what’s the next level? How do I push this even further?

Once it became clear that this was an opportunity to try multiple agents working together it graduated to an official Cursor research project, and available resources were amplified.

The goal of FastRender was never to build a browser to compete with the likes of Chrome. 41:52

We never intended for it to be a production software or usable, but we wanted to observe behaviors of this harness of multiple agents, to see how they could work at scale.

The great thing about a browser is that it has such a large scope that it can keep serving experiments in this space for many years to come. JavaScript, then WebAssembly, then WebGPU... it could take many years to run out of new challenges for the agents to tackle.

Running thousands of agents at once

The most interesting thing about FastRender is the way the project used multiple agents working in parallel to build different parts of the browser. I asked how many agents were running at once: 05:24

At the peak, when we had the stable system running for one week continuously, there were approximately 2,000 agents running concurrently at one time. And they were making, I believe, thousands of commits per hour.

The project has nearly 30,000 commits!

How do you run 2,000 agents at once? They used really big machines. 05:56

The simple approach we took with the infrastructure was to have a large machine run one of these multi-agent harnesses. Each machine had ample resources, and it would run about 300 agents concurrently on each. This was able to scale and run reasonably well, as agents spend a lot of time thinking, and not just running tools.

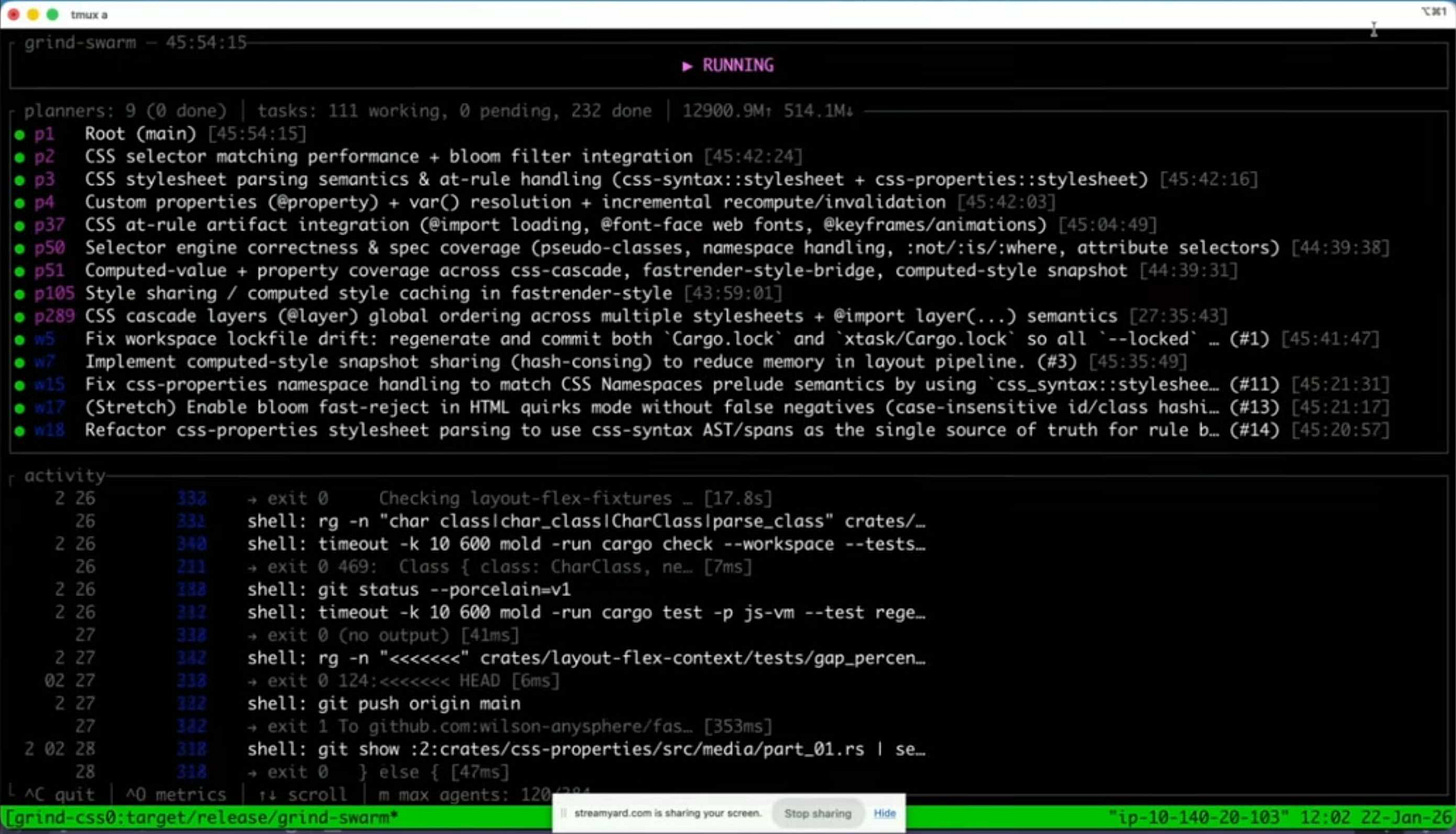

At this point we switched to a live demo of the harness running on one of those big machines (06:32). The agents are arranged in a tree structure, with planning agents firing up tasks and worker agents then carrying them out. 07:14

This cluster of agents is working towards building out the CSS aspects of the browser, whether that’s parsing, selector engine, those features. We managed to push this even further by splitting out the browser project into multiple instructions or work streams and have each one run one of these harnesses on their own machine, so that was able to further parallelize and increase throughput.

But don’t all of these agents working on the same codebase result in a huge amount of merge conflicts? Apparently not: 08:21

We’ve noticed that most commits do not have merge conflicts. The reason is the harness itself is able to quite effectively split out and divide the scope and tasks such that it tries to minimize the amount of overlap of work. That’s also reflected in the code structure—commits will be made at various times and they don’t tend to touch each other at the same time.

This appears to be the key trick for unlocking benefits from parallel agents: if planning agents do a good enough job of breaking up the work into non-overlapping chunks you can bring hundreds or even thousands of agents to bear on a problem at once.

Surprisingly, Wilson found that GPT-5.1 and GPT-5.2 were a better fit for this work than the coding specialist GPT-5.1-Codex: 17:28

Some initial findings were that the instructions here were more expansive than merely coding. For example, how to operate and interact within a harness, or how to operate autonomously without interacting with the user or having a lot of user feedback. These kinds of instructions we found worked better with the general models.

I asked what the longest they’ve seen this system run without human intervention: 18:28

So this system, once you give an instruction, there’s actually no way to steer it, you can’t prompt it, you’re going to adjust how it goes. The only thing you can do is stop it. So our longest run, all the runs are basically autonomous. We don’t alter the trajectory while executing. [...]

And so the longest at the time of the post was about a week and that’s pretty close to the longest. Of course the research project itself was only about three weeks so you know we probably can go longer.

Specifications and feedback loops

An interesting aspect of this project design is feedback loops. For agents to work autonomously for long periods of time they need as much useful context about the problem they are solving as possible, combined with effective feedback loops to help them make decisions.

The FastRender repo uses git submodules to include relevant specifications, including csswg-drafts, tc39-ecma262 for JavaScript, whatwg-dom, whatwg-html and more. 14:06

Feedback loops to the system are very important. Agents are working for very long periods continuously, and without guardrails and feedback to know whether what they’re doing is right or wrong it can have a big impact over a long rollout. Specs are definitely an important part—you can see lots of comments in the code base that AI wrote referring specifically to specs that they found in the specs submodules.

GPT-5.2 is a vision-capable model, and part of the feedback loop for FastRender included taking screenshots of the rendering results and feeding those back into the model: 16:23

In the earlier evolution of this project, when it was just doing the static renderings of screenshots, this was definitely a very explicit thing we taught it to do. And these models are visual models, so they do have that ability. We have progress indicators to tell it to compare the diff against a golden sample.

The strictness of the Rust compiler helped provide a feedback loop as well: 15:52

The nice thing about Rust is you can get a lot of verification just from compilation, and that is not as available in other languages.

The agents chose the dependencies

We talked about the Cargo.toml dependencies that the project had accumulated, almost all of which had been selected by the agents themselves.

Some of these, like Skia for 2D graphics rendering or HarfBuzz for text shaping, were obvious choices. Others such as Taffy felt like they might go against the from-scratch goals of the project, since that library implements CSS flexbox and grid layout algorithms directly. This was not an intended outcome. 27:53

Similarly these are dependencies that the agent picked to use for small parts of the engine and perhaps should have actually implemented itself. I think this reflects on the importance of the instructions, because I actually never encoded specifically the level of dependencies we should be implementing ourselves.

The agents vendored in Taffy and applied a stream of changes to that vendored copy. 31:18

It’s currently vendored. And as the agents work on it, they do make changes to it. This was actually an artifact from the very early days of the project before it was a fully fledged browser... it’s implementing things like the flex and grid layers, but there are other layout methods like inline, block, and table, and in our new experiment, we’re removing that completely.

The inclusion of QuickJS despite the presence of a home-grown ecma-rs implementation has a fun origin story: 35:15

I believe it mentioned that it pulled in the QuickJS because it knew that other agents were working on the JavaScript engine, and it needed to unblock itself quickly. [...]

It was like, eventually, once that’s finished, let’s remove it and replace with the proper engine.

I love how similar this is to the dynamics of a large-scale human engineering team, where you could absolutely see one engineer getting frustrated at another team not having delivered yet and unblocking themselves by pulling in a third-party library.

Intermittent errors are OK, actually

Here’s something I found really surprising: the agents were allowed to introduce small errors into the codebase as they worked! 39:42

One of the trade-offs was: if you wanted every single commit to be a hundred percent perfect, make sure it can always compile every time, that might be a synchronization bottleneck. [...]

Especially as you break up the system into more modularized aspects, you can see that errors get introduced, but small errors, right? An API change or some syntax error, but then they get fixed really quickly after a few commits. So there’s a little bit of slack in the system to allow these temporary errors so that the overall system can continue to make progress at a really high throughput. [...]

People may say, well, that’s not correct code. But it’s not that the errors are accumulating. It’s a stable rate of errors. [...] That seems like a worthwhile trade-off.

If you’re going to have thousands of agents working in parallel optimizing for throughput over correctness turns out to be a strategy worth exploring.

A single engineer plus a swarm of agents in January 2026

The thing I find most interesting about FastRender is how it demonstrates the extreme edge of what a single engineer can achieve in early 2026 with the assistance of a swarm of agents.

FastRender may not be a production-ready browser, but it represents over a million lines of Rust code, written in a few weeks, that can already render real web pages to a usable degree.

A browser really is the ideal research project to experiment with this new, weirdly shaped form of software engineering.

I asked Wilson how much mental effort he had invested in browser rendering compared to agent co-ordination. 11:34

The browser and this project were co-developed and very symbiotic, only because the browser was a very useful objective for us to measure and iterate the progress of the harness. The goal was to iterate on and research the multi-agent harness—the browser was just the research example or objective.

FastRender is effectively using a full browser rendering engine as a “hello world” exercise for multi-agent coordination!

Link 2026-01-13 Anthropic invests $1.5 million in the Python Software Foundation and open source security:

This is outstanding news, especially given our decision to withdraw from that NSF grant application back in October.

We are thrilled to announce that Anthropic has entered into a two-year partnership with the Python Software Foundation (PSF) to contribute a landmark total of $1.5 million to support the foundation’s work, with an emphasis on Python ecosystem security. This investment will enable the PSF to make crucial security advances to CPython and the Python Package Index (PyPI) benefiting all users, and it will also sustain the foundation’s core work supporting the Python language, ecosystem, and global community.

Note that while security is a focus these funds will also support other aspects of the PSF’s work:

Anthropic’s support will also go towards the PSF’s core work, including the Developer in Residence program driving contributions to CPython, community support through grants and other programs, running core infrastructure such as PyPI, and more.

Link 2026-01-14 Claude Cowork Exfiltrates Files:

Claude Cowork defaults to allowing outbound HTTP traffic to only a specific list of domains, to help protect the user against prompt injection attacks that exfiltrate their data.

Prompt Armor found a creative workaround: Anthropic’s API domain is on that list, so they constructed an attack that includes an attacker’s own Anthropic API key and has the agent upload any files it can see to the https://api.anthropic.com/v1/files endpoint, allowing the attacker to retrieve their content later.

Quote 2026-01-15

When we optimize responses using a reward model as a proxy for “goodness” in reinforcement learning, models sometimes learn to “hack” this proxy and output an answer that only “looks good” to it (because coming up with an answer that is actually good can be hard). The philosophy behind confessions is that we can train models to produce a second output — aka a “confession” — that is rewarded solely for honesty, which we will argue is less likely hacked than the normal task reward function. One way to think of confessions is that we are giving the model access to an “anonymous tip line” where it can turn itself in by presenting incriminating evidence of misbehavior. But unlike real-world tip lines, if the model acted badly in the original task, it can collect the reward for turning itself in while still keeping the original reward from the bad behavior in the main task. We hypothesize that this form of training will teach models to produce maximally honest confessions.

Boaz Barak, Gabriel Wu, Jeremy Chen and Manas Joglekar, OpenAI: Why we are excited about confessions

Link 2026-01-15 The Design & Implementation of Sprites:

I wrote about Sprites last week. Here’s Thomas Ptacek from Fly with the insider details on how they work under the hood.

I like this framing of them as “disposable computers”:

Sprites are ball-point disposable computers. Whatever mark you mean to make, we’ve rigged it so you’re never more than a second or two away from having a Sprite to do it with.

I’ve noticed that new Fly Machines can take a while (up to around a minute) to provision. Sprites solve that by keeping warm pools of unused machines in multiple regions, which is enabled by them all using the same container:

Now, today, under the hood, Sprites are still Fly Machines. But they all run from a standard container. Every physical worker knows exactly what container the next Sprite is going to start with, so it’s easy for us to keep pools of “empty” Sprites standing by. The result: a Sprite create doesn’t have any heavy lifting to do; it’s basically just doing the stuff we do when we start a Fly Machine.

The most interesting detail is how the persistence layer works. Sprites only charge you for data you have written that differs from the base image and provide ~300ms checkpointing and restores - it turns out that’s power by a custom filesystem on top of S3-compatible storage coordinated by Litestream-replicated local SQLite metadata:

We still exploit NVMe, but not as the root of storage. Instead, it’s a read-through cache for a blob on object storage. S3-compatible object stores are the most trustworthy storage technology we have. I can feel my blood pressure dropping just typing the words “Sprites are backed by object storage.” [...]

The Sprite storage stack is organized around the JuiceFS model (in fact, we currently use a very hacked-up JuiceFS, with a rewritten SQLite metadata backend). It works by splitting storage into data (“chunks”) and metadata (a map of where the “chunks” are). Data chunks live on object stores; metadata lives in fast local storage. In our case, that metadata store is kept durable with Litestream. Nothing depends on local storage.

Link 2026-01-15 Open Responses:

This is the standardization effort I’ve most wanted in the world of LLMs: a vendor-neutral specification for the JSON API that clients can use to talk to hosted LLMs.

Open Responses aims to provide exactly that as a documented standard, derived from OpenAI’s Responses API.

I was hoping for one based on their older Chat Completions API since so many other products have cloned the already, but basing it on Responses does make sense since that API was designed with the feature of more recent models - such as reasoning traces - baked into the design.

What’s certainly notable is the list of launch partners. OpenRouter alone means we can expect to be able to use this protocol with almost every existing model, and Hugging Face, LM Studio, vLLM, Ollama and Vercel cover a huge portion of the common tools used to serve models.

For protocols like this I really want to see a comprehensive, language-independent conformance test site. Open Responses has a subset of that - the official repository includes src/lib/compliance-tests.ts which can be used to exercise a server implementation, and is available as a React app on the official site that can be pointed at any implementation served via CORS.

What’s missing is the equivalent for clients. I plan to spin up my own client library for this in Python and I’d really like to be able to run that against a conformance suite designed to check that my client correctly handles all of the details.

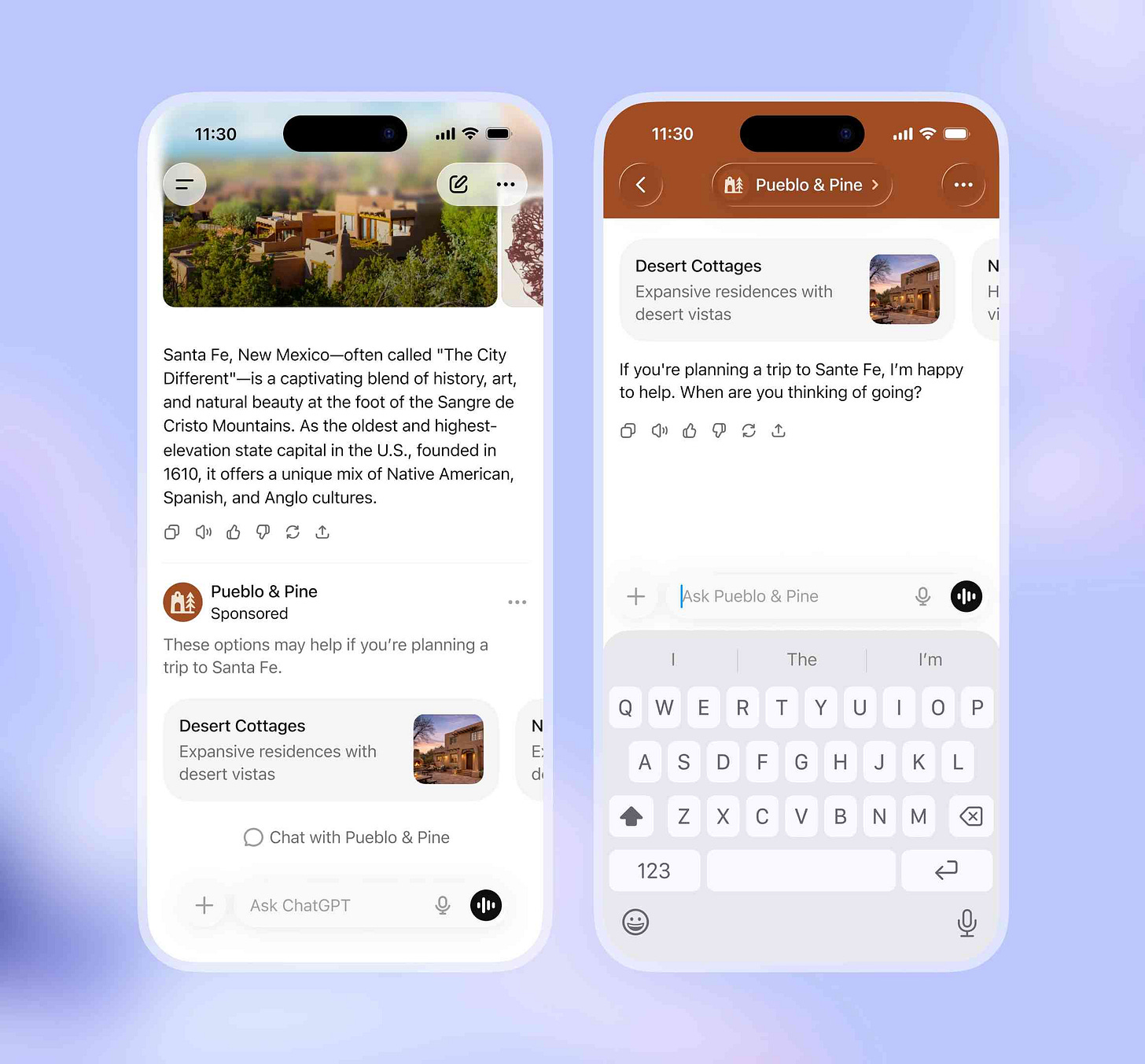

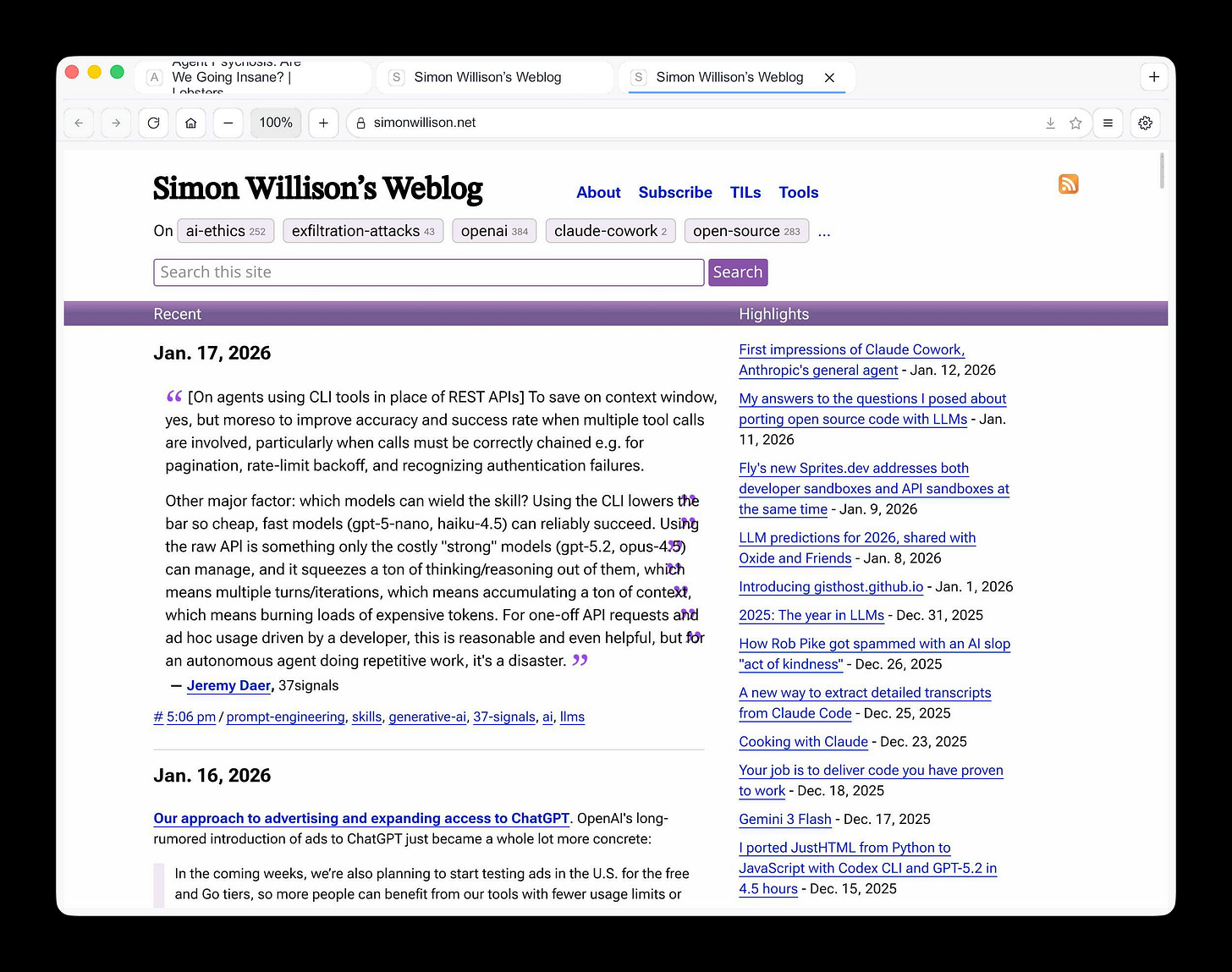

Link 2026-01-16 Our approach to advertising and expanding access to ChatGPT:

OpenAI’s long-rumored introduction of ads to ChatGPT just became a whole lot more concrete:

In the coming weeks, we’re also planning to start testing ads in the U.S. for the free and Go tiers, so more people can benefit from our tools with fewer usage limits or without having to pay. Plus, Pro, Business, and Enterprise subscriptions will not include ads.

What’s “Go” tier, you might ask? That’s a new $8/month tier that launched today in the USA, see Introducing ChatGPT Go, now available worldwide. It’s a tier that they first trialed in India in August 2025 (here’s a mention in their release notes from August listing a price of ₹399/month, which converts to around $4.40).

I’m finding the new plan comparison grid on chatgpt.com/pricing pretty confusing. It lists all accounts as having access to GPT-5.2 Thinking, but doesn’t clarify the limits that the free and Go plans have to conform to. It also lists different context windows for the different plans - 16K for free, 32K for Go and Plus and 128K for Pro. I had assumed that the 400,000 token window on the GPT-5.2 model page applied to ChatGPT as well, but apparently I was mistaken.

Update: I’ve apparently not been paying attention: here’s the Internet Archive ChatGPT pricing page from September 2025 showing those context limit differences as well.

Back to advertising: my biggest concern has always been whether ads will influence the output of the chat directly. OpenAI assure us that they will not:

Answer independence: Ads do not influence the answers ChatGPT gives you. Answers are optimized based on what’s most helpful to you. Ads are always separate and clearly labeled.

Conversation privacy: We keep your conversations with ChatGPT private from advertisers, and we never sell your data to advertisers.

So what will they look like then? This screenshot from the announcement offers a useful hint:

The user asks about trips to Santa Fe, and an ad shows up for a cottage rental business there. This particular example imagines an option to start a direct chat with a bot aligned with that advertiser, at which point presumably the advertiser can influence the answers all they like!

Quote 2026-01-17

*[On agents using CLI tools in place of REST APIs]* To save on context window, yes, but moreso to improve accuracy and success rate when multiple tool calls are involved, particularly when calls must be correctly chained e.g. for pagination, rate-limit backoff, and recognizing authentication failures.

Other major factor: which models can wield the skill? Using the CLI lowers the bar so cheap, fast models (gpt-5-nano, haiku-4.5) can reliably succeed. Using the raw APl is something only the costly “strong” models (gpt-5.2, opus-4.5) can manage, and it squeezes a ton of thinking/reasoning out of them, which means multiple turns/iterations, which means accumulating a ton of context, which means burning loads of expensive tokens. For one-off API requests and ad hoc usage driven by a developer, this is reasonable and even helpful, but for an autonomous agent doing repetitive work, it’s a disaster.

Jeremy Daer, 37signals

Link 2026-01-18 FLUX.2-klein-4B Pure C Implementation:

On 15th January Black Forest Labs, a lab formed by the creators of the original Stable Diffusion, released black-forest-labs/FLUX.2-klein-4B - an Apache 2.0 licensed 4 billion parameter version of their FLUX.2 family.

Salvatore Sanfilippo (antirez) decided to build a pure C and dependency-free implementation to run the model, with assistance from Claude Code and Claude Opus 4.5.

Salvatore shared this note on Hacker News:

Something that may be interesting for the reader of this thread: this project was possible only once I started to tell Opus that it needed to take a file with all the implementation notes, and also accumulating all the things we discovered during the development process. And also, the file had clear instructions to be taken updated, and to be processed ASAP after context compaction. This kinda enabled Opus to do such a big coding task in a reasonable amount of time without loosing track. Check the file IMPLEMENTATION_NOTES.md in the GitHub repo for more info.

Here’s that IMPLEMENTATION_NOTES.md file.

Link 2026-01-19 Scaling long-running autonomous coding:

Wilson Lin at Cursor has been doing some experiments to see how far you can push a large fleet of “autonomous” coding agents:

This post describes what we’ve learned from running hundreds of concurrent agents on a single project, coordinating their work, and watching them write over a million lines of code and trillions of tokens.

They ended up running planners and sub-planners to create tasks, then having workers execute on those tasks - similar to how Claude Code uses sub-agents. Each cycle ended with a judge agent deciding if the project was completed or not.

In my predictions for 2026 the other day I said that by 2029:

I think somebody will have built a full web browser mostly using AI assistance, and it won’t even be surprising. Rolling a new web browser is one of the most complicated software projects I can imagine[...] the cheat code is the conformance suites. If there are existing tests that it’ll get so much easier.

I may have been off by three years, because Cursor chose “building a web browser from scratch” as their test case for their agent swarm approach:

To test this system, we pointed it at an ambitious goal: building a web browser from scratch. The agents ran for close to a week, writing over 1 million lines of code across 1,000 files. You can explore the source code on GitHub.

But how well did they do? Their initial announcement a couple of days ago was met with unsurprising skepticism, especially when it became apparent that their GitHub Actions CI was failing and there were no build instructions in the repo.

It looks like they addressed that within the past 24 hours. The latest README includes build instructions which I followed on macOS like this:

cd /tmp

git clone https://github.com/wilsonzlin/fastrender

cd fastrender

git submodule update --init vendor/ecma-rs

cargo run --release --features browser_ui --bin browserThis got me a working browser window! Here are screenshots I took of google.com and my own website:

Honestly those are very impressive! You can tell they’re not just wrapping an existing rendering engine because of those very obvious rendering glitches, but the pages are legible and look mostly correct.

The FastRender repo even uses Git submodules to include various WhatWG and CSS-WG specifications in the repo, which is a smart way to make sure the agents have access to the reference materials that they might need.

This is the second attempt I’ve seen at building a full web browser using AI-assisted coding in the past two weeks - the first was HiWave browser, a new browser engine in Rust first announced in this Reddit thread.

When I made my 2029 prediction this is more-or-less the quality of result I had in mind. I don’t think we’ll see projects of this nature compete with Chrome or Firefox or WebKit any time soon but I have to admit I’m very surprised to see something this capable emerge so quickly.

Link 2026-01-19 jordanhubbard/nanolang:

Plenty of people have mused about what a new programming language specifically designed to be used by LLMs might look like. Jordan Hubbard (co-founder of FreeBSD, with serious stints at Apple and NVIDIA) just released exactly that.

A minimal, LLM-friendly programming language with mandatory testing and unambiguous syntax.

NanoLang transpiles to C for native performance while providing a clean, modern syntax optimized for both human readability and AI code generation.

The syntax strikes me as an interesting mix between C, Lisp and Rust.

I decided to see if an LLM could produce working code in it directly, given the necessary context. I started with this MEMORY.md file, which begins:

Purpose: This file is designed specifically for Large Language Model consumption. It contains the essential knowledge needed to generate, debug, and understand NanoLang code. Pair this with

spec.jsonfor complete language coverage.

I ran that using LLM and llm-anthropic like this:

llm -m claude-opus-4.5 \

-s https://raw.githubusercontent.com/jordanhubbard/nanolang/refs/heads/main/MEMORY.md \

'Build me a mandelbrot fractal CLI tool in this language'

> /tmp/fractal.nanoThe resulting code... did not compile.

I may have been too optimistic expecting a one-shot working program for a new language like this. So I ran a clone of the actual project, copied in my program and had Claude Code take a look at the failing compiler output.

... and it worked! Claude happily grepped its way through the various examples/ and built me a working program.

Here’s the Claude Code transcript - you can see it reading relevant examples here - and here’s the finished code plus its output.

I’ve suspected for a while that LLMs and coding agents might significantly reduce the friction involved in launching a new language. This result reinforces my opinion.

Link 2026-01-20 Giving University Exams in the Age of Chatbots:

Detailed and thoughtful description of an open-book and open-chatbot exam run by Ploum at École Polytechnique de Louvain for an “Open Source Strategies” class.

Students were told they could use chatbots during the exam but they had to announce their intention to do so in advance, share their prompts and take full accountability for any mistakes they made.

Only 3 out of 60 students chose to use chatbots. Ploum surveyed half of the class to help understand their motivations.

Link 2026-01-20 Electricity use of AI coding agents:

Previous work estimating the energy and water cost of LLMs has generally focused on the cost per prompt using a consumer-level system such as ChatGPT.

Simon P. Couch notes that coding agents such as Claude Code use way more tokens in response to tasks, often burning through many thousands of tokens of many tool calls.

As a heavy Claude Code user, Simon estimates his own usage at the equivalent of 4,400 “typical queries” to an LLM, for an equivalent of around $15-$20 in daily API token spend. He figures that to be about the same as running a dishwasher once or the daily energy used by a domestic refrigerator.

Link 2026-01-21 Claude’s new constitution:

Late last year Richard Weiss found something interesting while poking around with the just-released Claude Opus 4.5: he was able to talk the model into regurgitating a document which was not part of the system prompt but appeared instead to be baked in during training, and which described Claude’s core values at great length.

He called this leak the soul document, and Amanda Askell from Anthropic quickly confirmed that it was indeed part of Claude’s training procedures.

Today Anthropic made this official, releasing that full “constitution” document under a CC0 (effectively public domain) license. There’s a lot to absorb! It’s over 35,000 tokens, more than 10x the length of the published Opus 4.5 system prompt.

One detail that caught my eye is the acknowledgements at the end, which include a list of external contributors who helped review the document. I was intrigued to note that two of the fifteen listed names are Catholic members of the clergy - Father Brendan McGuire is a pastor in Los Altos with a Master’s degree in Computer Science and Math and Bishop Paul Tighe is an Irish Catholic bishop with a background in moral theology.

Quote 2026-01-22

Most people’s mental model of Claude Code is that “it’s just a TUI” but it should really be closer to “a small game engine”.

For each frame our pipeline constructs a scene graph with React then:

-> layout elements

-> rasterize them to a 2d screen

-> diff that against the previous screen

-> *finally* use the diff to generate ANSI sequences to draw

We have a ~16ms frame budget so we have roughly ~5ms to go from the React scene graph to ANSI written.

Chris Lloyd, Claude Code team at Anthropic

TIL 2026-01-22 Previewing Claude Code for web branches with GitHub Pages:

I’m a big user of Claude Code on the web, Anthropic’s poorly named cloud-based version of Claude Code which can be driven via the web or their native mobile and desktop applications. …

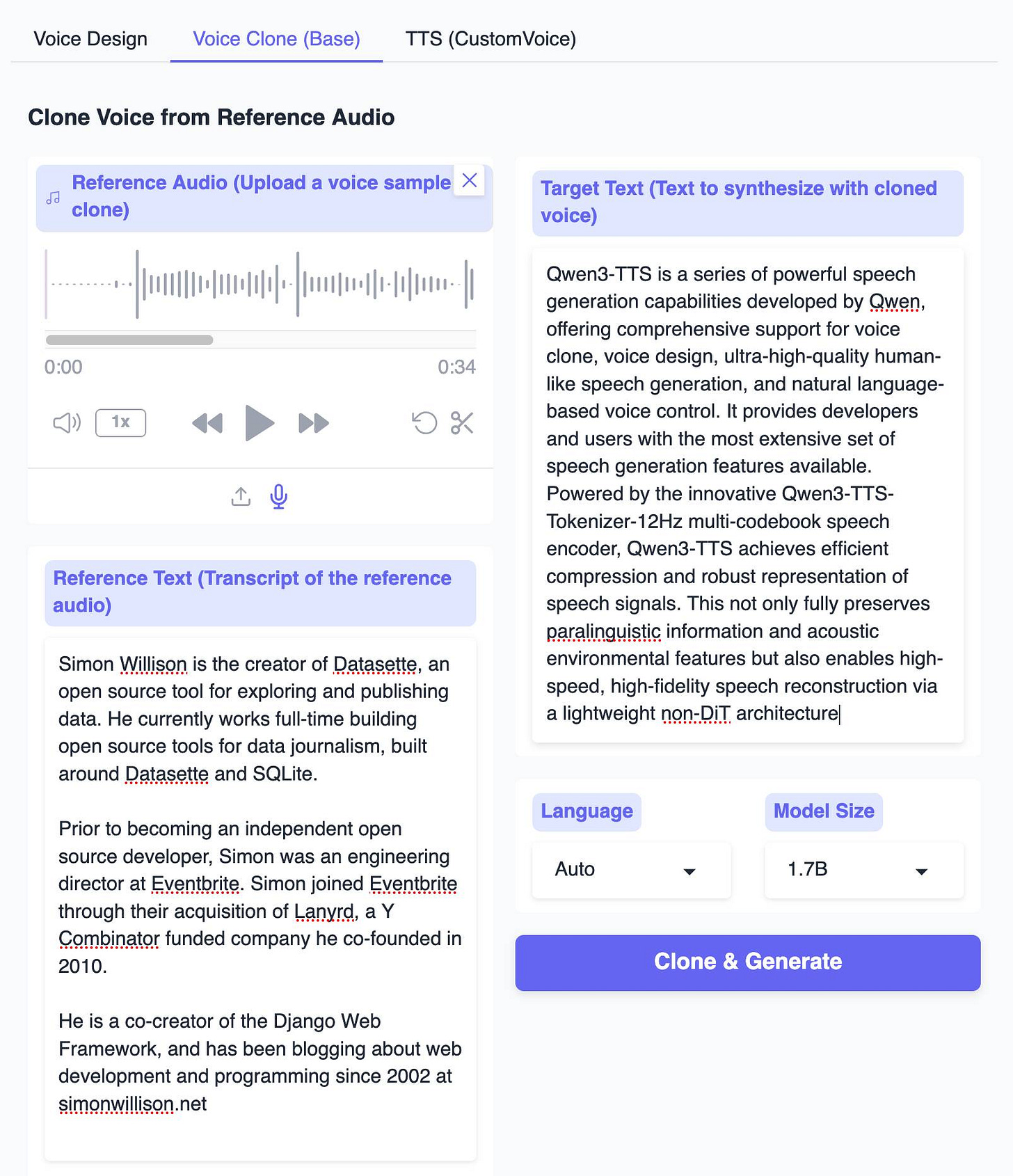

Link 2026-01-22 Qwen3-TTS Family is Now Open Sourced: Voice Design, Clone, and Generation:

I haven’t been paying much attention to the state-of-the-art in speech generation models other than noting that they’ve got really good, so I can’t speak for how notable this new release from Qwen is.

From the accompanying paper:

In this report, we present the Qwen3-TTS series, a family of advanced multilingual, controllable, robust, and streaming text-to-speech models. Qwen3-TTS supports state-of- the-art 3-second voice cloning and description-based control, allowing both the creation of entirely novel voices and fine-grained manipulation over the output speech. Trained on over 5 million hours of speech data spanning 10 languages, Qwen3-TTS adopts a dual-track LM architecture for real-time synthesis [...]. Extensive experiments indicate state-of-the-art performance across diverse objective and subjective benchmark (e.g., TTS multilingual test set, InstructTTSEval, and our long speech test set). To facilitate community research and development, we release both tokenizers and models under the Apache 2.0 license.

To give an idea of size, Qwen/Qwen3-TTS-12Hz-1.7B-Base is 4.54GB on Hugging Face and Qwen/Qwen3-TTS-12Hz-0.6B-Base is 2.52GB.

The Hugging Face demo lets you try out the 0.6B and 1.7B models for free in your browser, including voice cloning:

I tried this out by recording myself reading my about page and then having Qwen3-TTS generate audio of me reading the Qwen3-TTS announcement post. Here’s the result:

Your browser does not support the audio element.

It’s important that everyone understands that voice cloning is now something that’s available to anyone with a GPU and a few GBs of VRAM... or in this case a web browser that can access Hugging Face.

Update: Prince Canuma got this working with his mlx-audio library. I had Claude turn that into a CLI tool which you can run with uv ike this:

uv run https://tools.simonwillison.net/python/q3_tts.py \

'I am a pirate, give me your gold!' \

-i 'gruff voice' -o pirate.wavThe -i option lets you use a prompt to describe the voice it should use. On first run this downloads a 4.5GB model file from Hugging Face.

Link 2026-01-22 SSH has no Host header:

exe.dev is a new hosting service that, for $20/month, gives you up to 25 VMs “that share 2 CPUs and 8GB RAM”. Everything happens over SSH, including creating new VMs. Once configured you can sign into your exe.dev VMs like this:

ssh simon.exe.devHere’s the clever bit: when you run the above command exe.dev signs you into your VM of that name... but they don’t assign every VM its own IP address and SSH has no equivalent of the Host header, so how does their load balancer know which of your VMs to forward you on to?

The answer is that while they don’t assign a unique IP to every VM they do have enough IPs that they can ensure each of your VMs has an IP that is unique to your account.

If I create two VMs they will each resolve to a separate IP address, each of which is shared with many other users. The underlying infrastructure then identifies my user account from my SSH public key and can determine which underlying VM to forward my SSH traffic to.

Quote 2026-01-23

[...] i was too busy with work to read anything, so i asked chatgpt to summarize some books on state formation, and it suggested circumscription theory. there was already the natural boundary of my computer hemming the towns in, and town mayors played the role of big men to drive conflict. so i just needed a way for them to fight. i slightly tweaked the allocation of claude max accounts to the towns from a demand-based to a fixed allocation system. towns would each get a fixed amount of tokens to start, but i added a soldier role that could attack and defend in raids to steal tokens from other towns. [...]

Theia Vogel, Gas Town fan fiction

TIL 2026-01-23 Cloudflare response header transform rules:

I serve Python files from my tools.simonwillison.net subdomain, which is a GitHub Pages site that’s served via Cloudflare. For example: …

The fact that FastRender's agents tackled CSS Grid implementation through the Taffy library is particularly interesting from an architectural perspective. CSS Grid represents one of the most complex layout specifications in modern web standards, requiring sophisticated constraint solving and box model calculations.

What stands out is the agents' pragmatic decision to vendor and modify Taffy rather than implementing grid layout from scratch - showing a form of "engineering judgment" that mirrors human developer behavior. The tension between building everything from first principles versus leveraging existing solutions is something every browser team navigates.

I'm curious whether the agents had any particular struggles with CSS Grid's auto-placement algorithm or the interaction between grid and other layout modes. These edge cases are where browser implementations typically diverge from spec.

It makes me wonder what the equivalent “FastRender‑style” project would be for other domains that creators and researchers care about but that don’t have decades of conformance tests to lean on.