ChatGPT Containers can now run bash, pip/npm install packages, and download files

Plus adding dynamic features to an aggressively cached website

In this newsletter:

ChatGPT Containers can now run bash, pip/npm install packages, and download files

Adding dynamic features to an aggressively cached website

Plus 6 links and 1 quotation and 1 note

If you find this newsletter useful, please consider sponsoring me via GitHub. $10/month and higher sponsors get a monthly newsletter with my summary of the most important trends of the past 30 days - here are previews from October and November.

ChatGPT Containers can now run bash, pip/npm install packages, and download files - 2026-01-26

One of my favourite features of ChatGPT is its ability to write and execute code in a container. This feature launched as ChatGPT Code Interpreter nearly three years ago, was half-heartedly rebranded to “Advanced Data Analysis” at some point and is generally really difficult to find detailed documentation about. Case in point: it appears to have had a massive upgrade at some point in the past few months, and I can’t find documentation about the new capabilities anywhere!

Here are the most notable new features:

ChatGPT can directly run Bash commands now. Previously it was limited to Python code only, although it could run shell commands via the Python

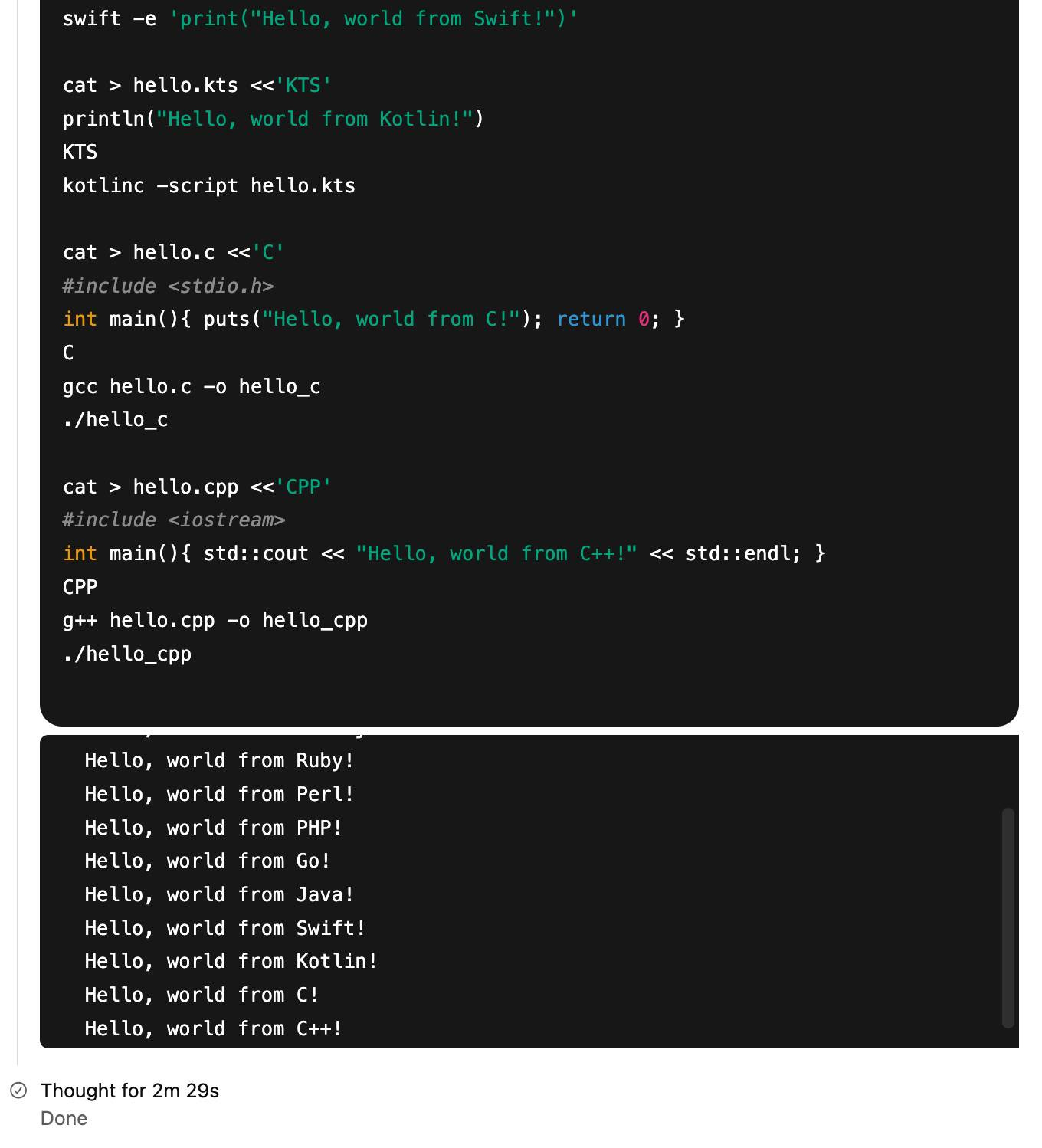

subprocessmodule.It has Node.js and can run JavaScript directly in addition to Python. I also got it to run “hello world” in Ruby, Perl, PHP, Go, Java, Swift, Kotlin, C and C++. No Rust yet though!

While the container still can’t make outbound network requests,

pip install packageandnpm install packageboth work now via a custom proxy mechanism.ChatGPT can locate the URL for a file on the web and use a

container.downloadtool to download that file and save it to a path within the sandboxed container.

This is a substantial upgrade! ChatGPT can now write and then test code in 10 new languages (11 if you count Bash), can find files online and download them into the container, and can install additional packages via pip and npm to help it solve problems.

(OpenAI really need to develop better habits at keeping their release notes up-to-date!)

I was initially suspicious that maybe I’d stumbled into a new preview feature that wasn’t available to everyone, but I tried some experiments in a free ChatGPT account and confirmed that the new features are available there as well.

container.download

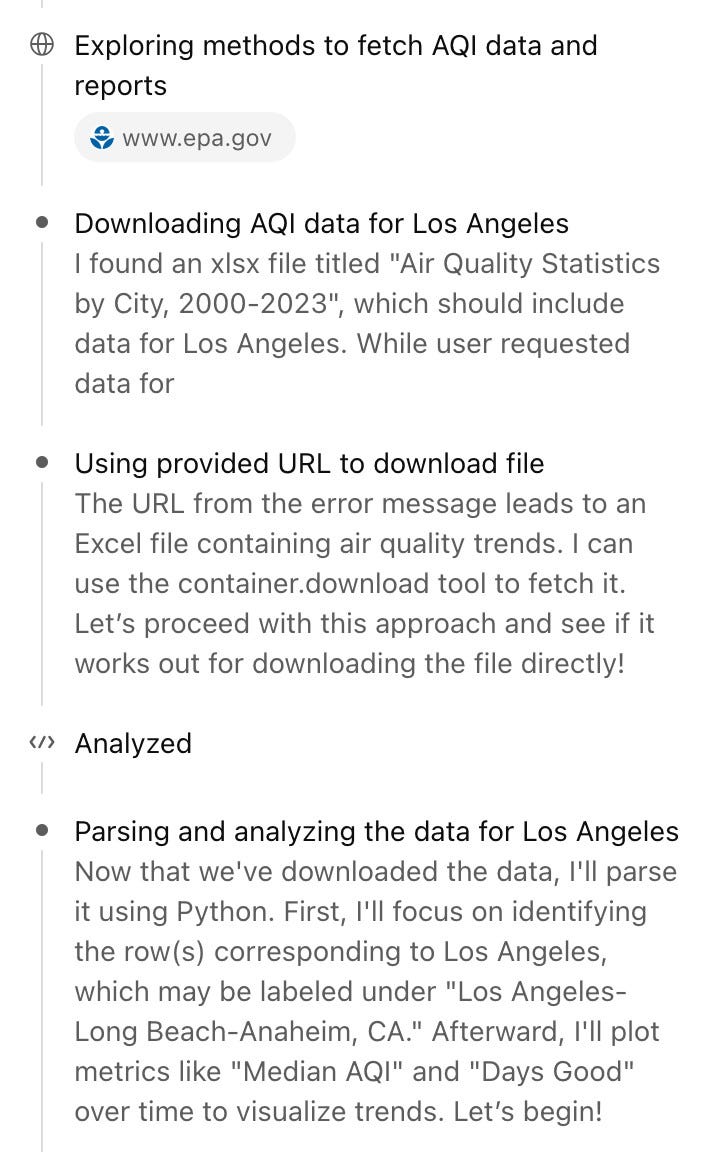

My first clue to the new features came the other day when I got curious about Los Angeles air quality, in particular has the growing number of electric vehicles there had a measurable impact?

I prompted a fresh GPT-5.2 Thinking session with:

Show me Los Angeles air quality over time for last 20 years

Here’s the shared transcript. Annoyingly that doesn’t make the thinking trace available, so here’s a screenshot:

This bit instantly caught my eye:

[...] The URL from the error message leads to an Excel file containing air quality trends. I can use the container.download tool to fetch it. [...]

What’s container.download? I asked ChatGPT:

Without running any searches tell me about your container.download tool

And got back:

Sure.

container.downloadis a built-in tool I can call that fetches a file from a URL and saves it into the sandboxed container filesystem for this chat session.What it does

Takes a publicly reachable URL and a destination filepath in the container.

Downloads the bytes from that URL and writes them to the given path.

After that, I can read/process the file locally in the container (e.g., unzip it, parse it with Python, open it as an image, convert it, etc.).

Signature (inputs)

It’s called like this (conceptually):

{ “url”: “https://example.com/somefile.zip”, “filepath”: “/mnt/data/somefile.zip” }

Further experimentation confirmed that container.download behaves as described.

I had it download one file from a server with logs enabled and captured the IP address and user-agent. Here are the most interesting headers:

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko); compatible; ChatGPT-User/1.0; +https://openai.com/bot

Accept: text/html, application/xhtml+xml, application/xml;q=0.9, image/avif, image/webp, image/apng, */*;q=0.8, application/signed-exchange;v=b3;q=0.9

Cf-Connecting-Ip: 52.230.164.178That 52.230.164.178 IP address resolves to Microsoft Azure Cloud (centralus) in Des Moines, Iowa.

Is container.download a data exfiltration vulnerability?

On the one hand, this is really useful! ChatGPT can navigate around websites looking for useful files, download those files to a container and then process them using Python or other languages.

Is this a data exfiltration vulnerability though? Could a prompt injection attack trick ChatGPT into leaking private data out to a container.download call to a URL with a query string that includes sensitive information?

I don’t think it can. I tried getting it to assemble a URL with a query string and access it using container.download and it couldn’t do it. It told me that it got back this error:

ERROR: download failed because url not viewed in conversation before. open the file or url using web.run first.

This looks to me like the same safety trick used by Claude’s Web Fetch tool: only allow URL access if that URL was either directly entered by the user or if it came from search results that could not have been influenced by a prompt injection.

(I poked at this a bit more and managed to get a simple constructed query string to pass through web.run - a different tool entirely - but when I tried to compose a longer query string containing the previous prompt history a web.run filter blocked it.)

So I think this is all safe, though I’m curious if it could hold firm against a more aggressive round of attacks from a seasoned security researcher.

Bash and other languages

The key lesson from coding agents like Claude Code and Codex CLI is that Bash rules everything: if an agent can run Bash commands in an environment it can do almost anything that can be achieved by typing commands into a computer.

When Anthropic added their own code interpreter feature to Claude last September they built that around Bash rather than just Python. It looks to me like OpenAI have now done the same thing for ChatGPT.

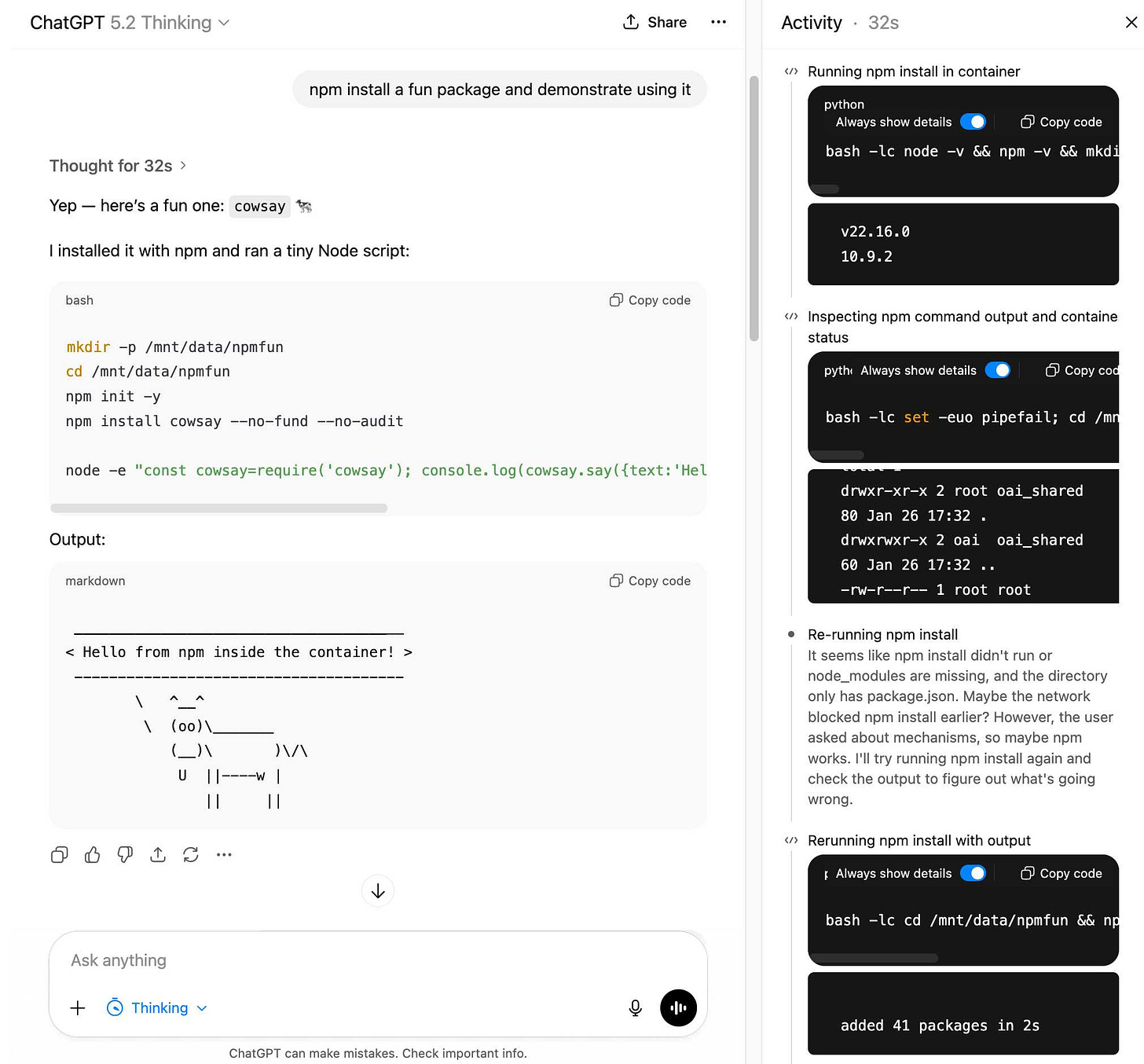

Here’s what ChatGPT looks like when it runs a Bash command - here my prompt was:

npm install a fun package and demonstrate using it

It’s useful to click on the “Thinking” or “Thought for 32s” links as that opens the Activity sidebar with a detailed trace of what ChatGPT did to arrive at its answer. This helps guard against cheating - ChatGPT might claim to have run Bash in the main window but it can’t fake those black and white logs in the Activity panel.

I had it run Hello World in various languages later in that same session.

Installing packages from pip and npm

In the previous example ChatGPT installed the cowsay package from npm and used it to draw an ASCII-art cow. But how could it do that if the container can’t make outbound network requests?

In another session I challenged it to explore its environment. and figure out how that worked.

Here’s the resulting Markdown report it created.

The key magic appears to be a applied-caas-gateway1.internal.api.openai.org proxy, available within the container and with various packaging tools configured to use it.

The following environment variables cause pip and uv to install packages from that proxy instead of directly from PyPI:

PIP_INDEX_URL=https://reader:****@packages.applied-caas-gateway1.internal.api.openai.org/.../pypi-public/simple

PIP_TRUSTED_HOST=packages.applied-caas-gateway1.internal.api.openai.org

UV_INDEX_URL=https://reader:****@packages.applied-caas-gateway1.internal.api.openai.org/.../pypi-public/simple

UV_INSECURE_HOST=https://packages.applied-caas-gateway1.internal.api.openai.orgThis one appears to get npm to work:

NPM_CONFIG_REGISTRY=https://reader:****@packages.applied-caas-gateway1.internal.api.openai.org/.../npm-publicAnd it reported these suspicious looking variables as well:

CAAS_ARTIFACTORY_BASE_URL=packages.applied-caas-gateway1.internal.api.openai.org

CAAS_ARTIFACTORY_PYPI_REGISTRY=.../artifactory/api/pypi/pypi-public

CAAS_ARTIFACTORY_NPM_REGISTRY=.../artifactory/api/npm/npm-public

CAAS_ARTIFACTORY_GO_REGISTRY=.../artifactory/api/go/golang-main

CAAS_ARTIFACTORY_MAVEN_REGISTRY=.../artifactory/maven-public

CAAS_ARTIFACTORY_GRADLE_REGISTRY=.../artifactory/gradle-public

CAAS_ARTIFACTORY_CARGO_REGISTRY=.../artifactory/api/cargo/cargo-public/index

CAAS_ARTIFACTORY_DOCKER_REGISTRY=.../dockerhub-public

CAAS_ARTIFACTORY_READER_USERNAME=reader

CAAS_ARTIFACTORY_READER_PASSWORD=****

NETWORK=caas_packages_onlyNeither Rust nor Docker are installed in the container environment, but maybe those registry references are a clue of features still to come.

Adding it all together

The result of all of this? You can tell ChatGPT to use Python or Node.js packages as part of a conversation and it will be able to install them and apply them against files you upload or that it downloads from the public web. That’s really cool.

The big missing feature here should be the easiest to provide: we need official documentation! A release notes entry would be a good start, but there are a lot of subtle details to how this new stuff works, its limitations and what it can be used for.

As always, I’d also encourage OpenAI to come up with a name for this set of features that properly represents how it works and what it can do.

In the meantime, I’m going to call this ChatGPT Containers.

Update: a full list of tools

I decided to ask ChatGPT about other tools that were available to it in case there was anything interesting in there:

List all tools that are available to you, with their exact names and descriptions and signatures

Here’s what I got back.

Adding dynamic features to an aggressively cached website - 2026-01-28

My blog uses aggressive caching: it sits behind Cloudflare with a 15 minute cache header, which guarantees it can survive even the largest traffic spike to any given page. I’ve recently added a couple of dynamic features that work in spite of that full-page caching. Here’s how those work.

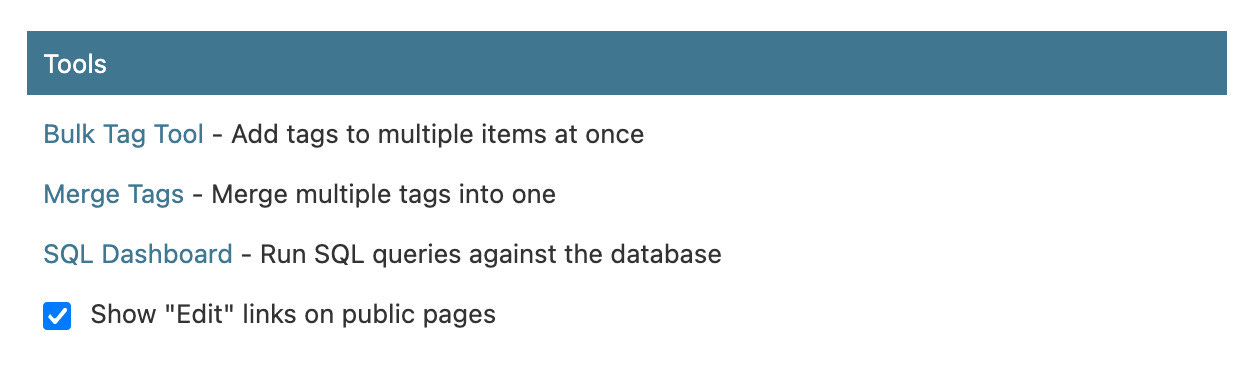

Edit links that are visible only to me

This is a Django site and I manage it through the Django admin.

I have four types of content - entries, link posts (aka blogmarks), quotations and notes. Each of those has a different model and hence a different Django admin area.

I wanted an “edit” link on the public pages that was only visible to me.

The button looks like this:

I solved conditional display of this button with localStorage. I have a tiny bit of JavaScript which checks to see if the localStorage key ADMIN is set and, if it is, displays an edit link based on a data attribute:

document.addEventListener(’DOMContentLoaded’, () => {

if (window.localStorage.getItem(’ADMIN’)) {

document.querySelectorAll(’.edit-page-link’).forEach(el => {

const url = el.getAttribute(’data-admin-url’);

if (url) {

const a = document.createElement(’a’);

a.href = url;

a.className = ‘edit-link’;

a.innerHTML = ‘<svg>...</svg> Edit’;

el.appendChild(a);

el.style.display = ‘block’;

}

});

}

});If you want to see my edit links you can run this snippet of JavaScript:

localStorage.setItem(’ADMIN’, ‘1’);My Django admin dashboard has a custom checkbox I can click to turn this option on and off in my own browser:

Random navigation within a tag

Those admin edit links are a very simple pattern. A more interesting one is a feature I added recently for navigating randomly within a tag.

Here’s an animated GIF showing those random tag navigations in action (try it here):

On any of my blog’s tag pages you can click the “Random” button to bounce to a random post with that tag. That random button then persists in the header of the page and you can click it to continue bouncing to random items in that same tag.

A post can have multiple tags, so there needs to be a little bit of persistent magic to remember which tag you are navigating and display the relevant button in the header.

Once again, this uses localStorage. Any click to a random button records both the tag and the current timestamp to the random_tag key in localStorage before redirecting the user to the /random/name-of-tag/ page, which selects a random post and redirects them there.

Any time a new page loads, JavaScript checks if that random_tag key has a value that was recorded within the past 5 seconds. If so, that random button is appended to the header.

This means that, provided the page loads within 5 seconds of the user clicking the button, the random tag navigation will persist on the page.

You can see the code for that here.

And the prompts

I built the random tag feature entirely using Claude Code for web, prompted from my iPhone. I started with the /random/TAG/ endpoint (full transcript):

Build /random/TAG/ - a page which picks a random post (could be an entry or blogmark or note or quote) that has that tag and sends a 302 redirect to it, marked as no-cache so Cloudflare does not cache it

Use a union to build a list of every content type (a string representing the table out of the four types) and primary key for every item tagged with that tag, then order by random and return the first one

Then inflate the type and ID into an object and load it and redirect to the URL

Include tests - it should work by setting up a tag with one of each of the content types and then running in a loop calling that endpoint until it has either returned one of each of the four types or it hits 1000 loops at which point fail with an error

Then:

I do not like that solution, some of my tags have thousands of items

Can we do something clever with a CTE?

Here’s the something clever with a CTE solution we ended up with.

For the “Random post” button (transcript):

Look at most recent commit, then modify the /tags/xxx/ page to have a “Random post” button which looks good and links to the /random/xxx/ page

Then:

Put it before not after the feed icon. It should only display if a tag has more than 5 posts

And finally, the localStorage implementation that persists a random tag button in the header (transcript):

Review the last two commits. Make it so clicking the Random button on a tag page sets a localStorage value for random_tag with that tag and a timestamp. On any other page view that uses the base item template add JS that checks for that localStorage value and makes sure the timestamp is within 5 seconds. If it is within 5 seconds it adds a “Random name-of-tag” button to the little top navigation bar, styled like the original Random button, which bumps the localStorage timestamp and then sends the user to /random/name-of-tag/ when they click it. In this way clicking “Random” on a tag page will send the user into an experience where they can keep clicking to keep surfing randomly in that topic.

Quote 2026-01-24

If you tell a friend they can now instantly create any app, they’ll probably say “Cool! Now I need to think of an idea.” Then they will forget about it, and never build a thing. The problem is not that your friend is horribly uncreative. It’s that most people’s problems are not software-shaped, and most won’t notice even when they are. [...]

Programmers are trained to see everything as a software-shaped problem: if you do a task three times, you should probably automate it with a script. Rename every IMG_*.jpg file from the last week to hawaii2025_*.jpg, they tell their terminal, while the rest of us painfully click and copy-paste. We are blind to the solutions we were never taught to see, asking for faster horses and never dreaming of cars.

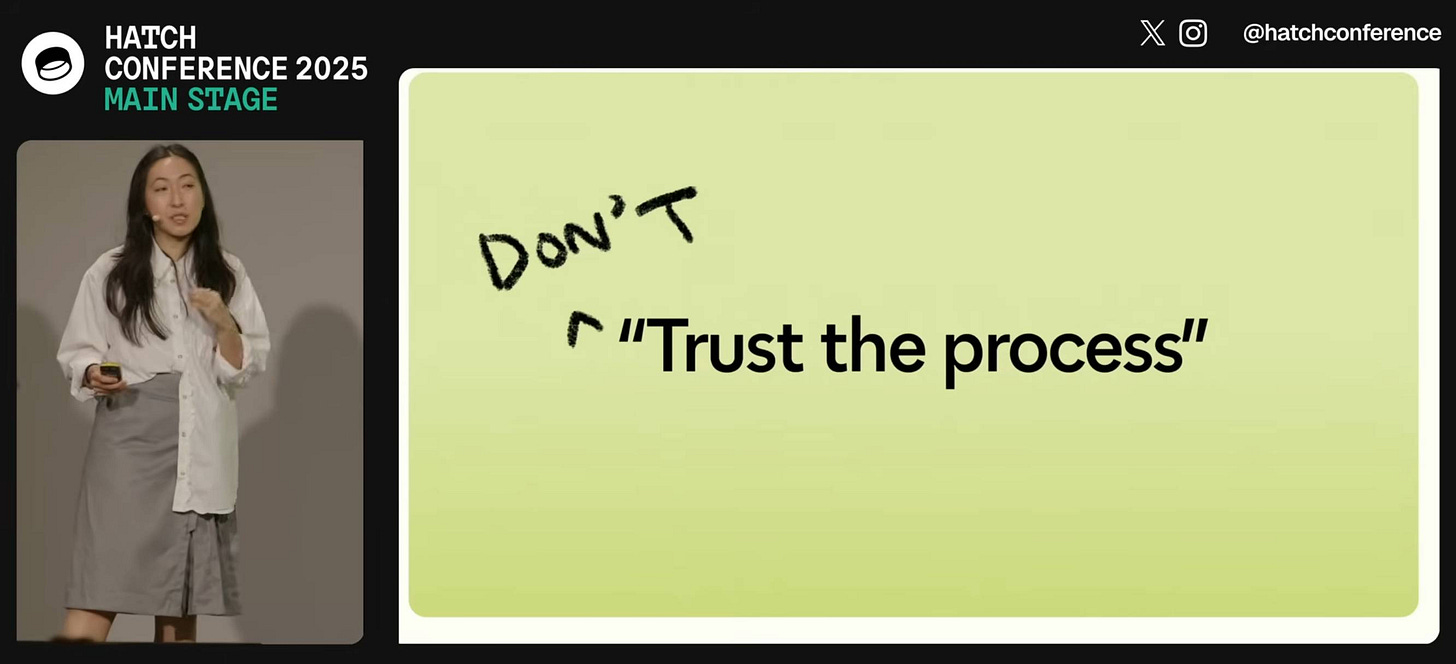

Link 2026-01-24 Don’t “Trust the Process”:

Jenny Wen, Design Lead at Anthropic (and previously Director of Design at Figma) gave a provocative keynote at Hatch Conference in Berlin last September.

Jenny argues that the Design Process - user research leading to personas leading to user journeys leading to wireframes... all before anything gets built - may be outdated for today’s world.

Hypothesis: In a world where anyone can make anything — what matters is your ability to choose and curate what you make.

In place of the Process, designers should lean into prototypes. AI makes these much more accessible and less time-consuming than they used to be.

Watching this talk made me think about how AI-assisted programming significantly reduces the cost of building the wrong thing. Previously if the design wasn’t right you could waste months of development time building in the wrong direction, which was a very expensive mistake. If a wrong direction wastes just a few days instead we can take more risks and be much more proactive in exploring the problem space.

I’ve always been a compulsive prototyper though, so this is very much playing into my own existing biases!

Link 2026-01-25 Kākāpō Cam: Rakiura live stream:

Critical update for this year’s Kākāpō breeding season: the New Zealand Department of Conservation have a livestream running of Rakiura’s nest!

You’re looking at the underground nest of 23-year-old Rakiura. She has chosen this same site to nest for all seven breeding seasons since 2008, a large cavity under a rātā tree. Because she returns to the site so reliably, we’ve been able to make modifications over the years to keep it safe and dry, including adding a well-placed hatch for monitoring eggs and chicks.

Rakiura is a legendary Kākāpō:

Rakiura hatched on 19 February 2002 on Whenua Hou/Codfish Island. She is the offspring of Flossie and Bill. Her name comes from the te reo Māori name for Stewart Island, the place where most of the founding kākāpō population originated.

Rakiura has nine living descendants, three females and six males, across six breeding seasons. In 2008 came Tōitiiti, in 2009 Tamahou and Te Atapō, in 2011 Tia and Tūtoko, in 2014 Taeatanga and Te Awa, in 2019 Mati-mā and Tautahi. She also has many grandchicks.

She laid her first egg of the season at 4:30pm NZ time on 22nd January. The livestream went live shortly afterwards, once she committed to this nest.

The stream is on YouTube. I used Claude Code to write a livestream-gif.py script and used that to capture this sped-up video of the last few hours of footage, within which you can catch a glimpse of the egg!

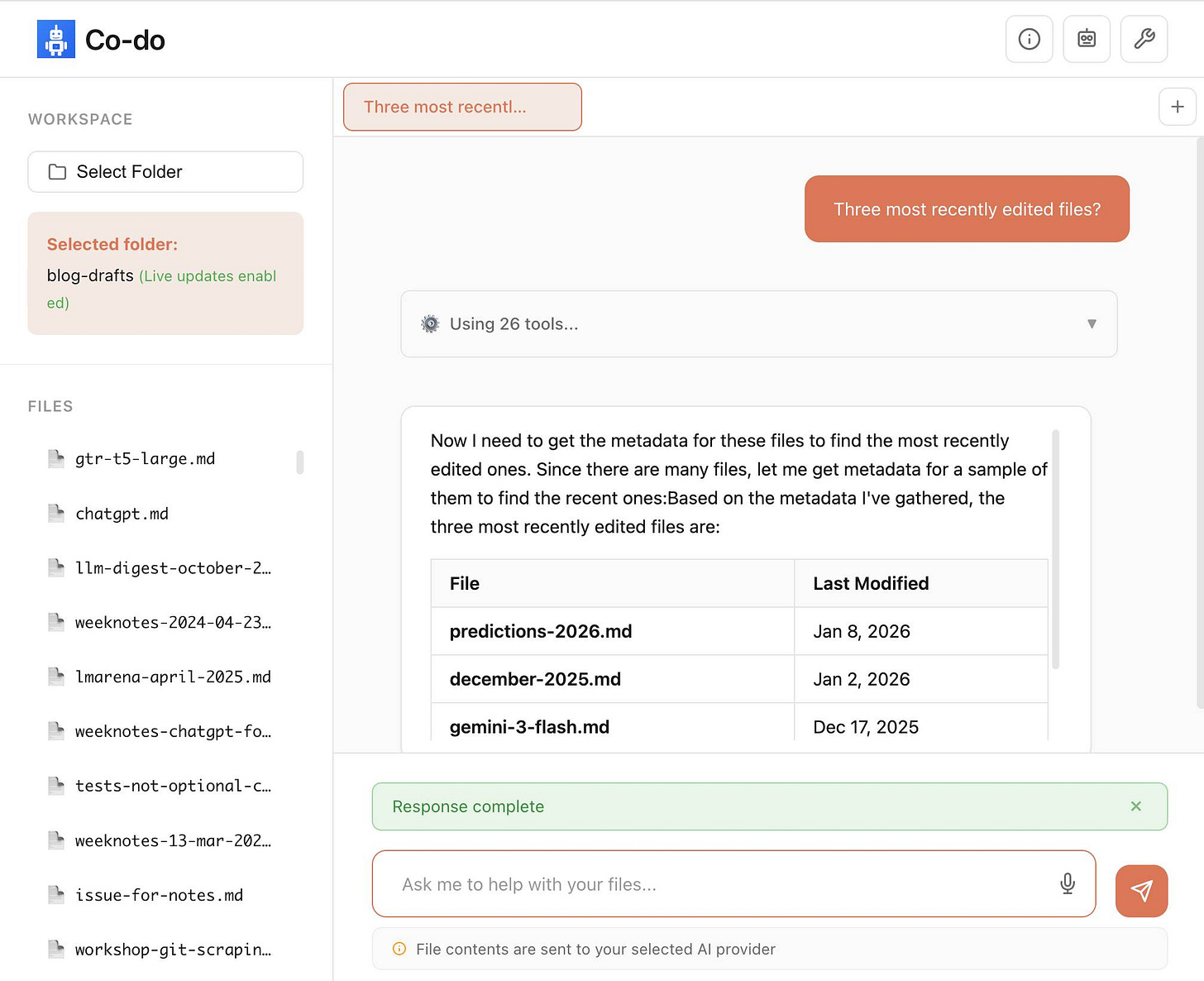

Link 2026-01-25 the browser is the sandbox:

Paul Kinlan is a web platform developer advocate at Google and recently turned his attention to coding agents. He quickly identified the importance of a robust sandbox for agents to operate in and put together these detailed notes on how the web browser can help:

This got me thinking about the browser. Over the last 30 years, we have built a sandbox specifically designed to run incredibly hostile, untrusted code from anywhere on the web, the instant a user taps a URL. [...]

Could you build something like Cowork in the browser? Maybe. To find out, I built a demo called Co-do that tests this hypothesis. In this post I want to discuss the research I’ve done to see how far we can get, and determine if the browser’s ability to run untrusted code is useful (and good enough) for enabling software to do more for us directly on our computer.

Paul then describes how the three key aspects of a sandbox - filesystem, network access and safe code execution - can be handled by browser technologies: the File System Access API (still Chrome-only as far as I can tell), CSP headers with <iframe sandbox> and WebAssembly in Web Workers.

Co-do is a very interesting demo that illustrates all of these ideas in a single application:

You select a folder full of files and configure an LLM provider and set an API key, Co-do then uses CSP-approved API calls to interact with that provider and provides a chat interface with tools for interacting with those files. It does indeed feel similar to Claude Cowork but without running a multi-GB local container to provide the sandbox.

My biggest complaint about <iframe sandbox> remains how thinly documented it is, especially across different browsers. Paul’s post has all sorts of useful details on that which I’ve not encountered elsewhere, including a complex double-iframe technique to help apply network rules to the inner of the two frames.

Thanks to this post I also learned about the <input type="file" webkitdirectory> tag which turns out to work on Firefox, Safari and Chrome and allows a browser read-only access to a full directory of files at once. I had Claude knock up a webkitdirectory demo to try it out and I’ll certainly be using it for projects in the future.

Note 2026-01-26

Someone asked on Hacker News if I had any tips for getting coding agents to write decent quality tests. Here’s what I said:

I work in Python which helps a lot because there are a TON of good examples of pytest tests floating around in the training data, including things like usage of fixture libraries for mocking external HTTP APIs and snapshot testing and other neat patterns.

Or I can say “use pytest-httpx to mock the endpoints” and Claude knows what I mean.

Keeping an eye on the tests is important. The most common anti-pattern I see is large amounts of duplicated test setup code - which isn’t a huge deal, I’m much more more tolerant of duplicated logic in tests than I am in implementation, but it’s still worth pushing back on.

“Refactor those tests to use pytest.mark.parametrize” and “extract the common setup into a pytest fixture” work really well there.

Generally though the best way to get good tests out of a coding agent is to make sure it’s working in a project with an existing test suite that uses good patterns. Coding agents pick the existing patterns up without needing any extra prompting at all.

I find that once a project has clean basic tests the new tests added by the agents tend to match them in quality. It’s similar to how working on large projects with a team of other developers work - keeping the code clean means when people look for examples of how to write a test they’ll be pointed in the right direction.

One last tip I use a lot is this:

Clone datasette/datasette-enrichments

from GitHub to /tmp and imitate the

testing patterns it usesI do this all the time with different existing projects I’ve written - the quickest way to show an agent how you like something to be done is to have it look at an example.

Link 2026-01-27 Kimi K2.5: Visual Agentic Intelligence:

Kimi K2 landed in July as a 1 trillion parameter open weight LLM. It was joined by Kimi K2 Thinking in November which added reasoning capabilities. Now they’ve made it multi-modal: the K2 models were text-only, but the new 2.5 can handle image inputs as well:

Kimi K2.5 builds on Kimi K2 with continued pretraining over approximately 15T mixed visual and text tokens. Built as a native multimodal model, K2.5 delivers state-of-the-art coding and vision capabilities and a self-directed agent swarm paradigm.

The “self-directed agent swarm paradigm” claim there means improved long-sequence tool calling and training on how to break down tasks for multiple agents to work on at once:

For complex tasks, Kimi K2.5 can self-direct an agent swarm with up to 100 sub-agents, executing parallel workflows across up to 1,500 tool calls. Compared with a single-agent setup, this reduces execution time by up to 4.5x. The agent swarm is automatically created and orchestrated by Kimi K2.5 without any predefined subagents or workflow.

I used the OpenRouter Chat UI to have it “Generate an SVG of a pelican riding a bicycle”, and it did quite well:

As a more interesting test, I decided to exercise the claims around multi-agent planning with this prompt:

I want to build a Datasette plugin that offers a UI to upload files to an S3 bucket and stores information about them in a SQLite table. Break this down into ten tasks suitable for execution by parallel coding agents.

Here’s the full response. It produced ten realistic tasks and reasoned through the dependencies between them. For comparison here’s the same prompt against Claude Opus 4.5 and against GPT-5.2 Thinking.

The Hugging Face repository is 595GB. The model uses Kimi’s janky “modified MIT” license, which adds the following clause:

Our only modification part is that, if the Software (or any derivative works thereof) is used for any of your commercial products or services that have more than 100 million monthly active users, or more than 20 million US dollars (or equivalent in other currencies) in monthly revenue, you shall prominently display “Kimi K2.5” on the user interface of such product or service.

Given the model’s size, I expect one way to run it locally would be with MLX and a pair of $10,000 512GB RAM M3 Ultra Mac Studios. That setup has been demonstrated to work with previous trillion parameter K2 models.

Link 2026-01-27 One Human + One Agent = One Browser From Scratch:

embedding-shapes was so infuriated by the hype around Cursor’s FastRender browser project - thousands of parallel agents producing ~1.6 million lines of Rust - that they were inspired to take a go at building a web browser using coding agents themselves.

The result is one-agent-one-browser and it’s really impressive. Over three days they drove a single Codex CLI agent to build 20,000 lines of Rust that successfully renders HTML+CSS with no Rust crate dependencies at all - though it does (reasonably) use Windows, macOS and Linux system frameworks for image and text rendering.

I installed the 1MB macOS binary release and ran it against my blog:

chmod 755 ~/Downloads/one-agent-one-browser-macOS-ARM64

~/Downloads/one-agent-one-browser-macOS-ARM64 https://simonwillison.net/Here’s the result:

It even rendered my SVG feed subscription icon! A PNG image is missing from the page, which looks like an intermittent bug (there’s code to render PNGs).

The code is pretty readable too - here’s the flexbox implementation.

I had thought that “build a web browser” was the ideal prompt to really stretch the capabilities of coding agents - and that it would take sophisticated multi-agent harnesses (as seen in the Cursor project) and millions of lines of code to achieve.

Turns out one agent driven by a talented engineer, three days and 20,000 lines of Rust is enough to get a very solid basic renderer working!

I’m going to upgrade my prediction for 2029: I think we’re going to get a production-grade web browser built by a small team using AI assistance by then.

Link 2026-01-28 The Five Levels: from Spicy Autocomplete to the Dark Factory:

Dan Shapiro proposes a five level model of AI-assisted programming, inspired by the five (or rather six, it’s zero-indexed) levels of driving automation.

Spicy autocomplete, aka original GitHub Copilot or copying and pasting snippets from ChatGPT.

The coding intern, writing unimportant snippets and boilerplate with full human review.

The junior developer, pair programming with the model but still reviewing every line.

The developer. Most code is generated by AI, and you take on the role of full-time code reviewer.

The engineering team. You’re more of an engineering manager or product/program/project manager. You collaborate on specs and plans, the agents do the work.

The dark software factory, like a factory run by robots where the lights are out because robots don’t need to see.

Dan says about that last category:

At level 5, it’s not really a car any more. You’re not really running anybody else’s software any more. And your software process isn’t really a software process any more. It’s a black box that turns specs into software.

Why Dark? Maybe you’ve heard of the Fanuc Dark Factory, the robot factory staffed by robots. It’s dark, because it’s a place where humans are neither needed nor welcome.

I know a handful of people who are doing this. They’re small teams, less than five people. And what they’re doing is nearly unbelievable -- and it will likely be our future.

I’ve talked to one team that’s doing the pattern hinted at here. It was fascinating. The key characteristics:

Nobody reviews AI-produced code, ever. They don’t even look at it.

The goal of the system is to prove that the system works. A huge amount of the coding agent work goes into testing and tooling and simulating related systems and running demos.

The role of the humans is to design that system - to find new patterns that can help the agents work more effectively and demonstrate that the software they are building is robust and effective.

It was a tiny team and they stuff they had built in just a few months looked very convincing to me. Some of them had 20+ years of experience as software developers working on systems with high reliability requirements, so they were not approaching this from a naive perspective.

I’m hoping they come out of stealth soon because I can’t really share more details than this.

When I asked ChatGPT to access a URL to check whether it could execute JavaScript, I noticed that, in addition to what you mentioned, it used jina.ai to fetch the content of my site. It seems to be a service from Jina that converts HTML into Markdown... and no, it doesn't render JavaScript.

Here’s a snippet from the response (spanish):

"content": {

"content_type": "thoughts",

"thoughts": [

{

"summary": "Intentando b\u00fasqueda alternativa",

"content": "Parece que no hay resultados para la URL que quer\u00eda. Entonces, intentar\u00e9 buscar otra opci\u00f3n con una consulta que incluya \"r.jina.ai/http://https://www.mecagoenlos.com/Posicionamiento/metodos-para-indexar-pginas.php\" para ver si consigo encontrar algo \u00fatil de esa manera.",

"chunks": [

"Parece que no hay resultados para la URL que quer\u00eda.",

"Entonces, intentar\u00e9 buscar otra opci\u00f3n con una consulta que incluya \"r.jina.ai/http://https://www.mecagoenlos.com/Posicionamiento/metodos-para-indexar-pginas.php\" para ver si consigo encontrar algo \u00fatil de esa manera."

],

"finished": true

}

],

...

...

"create_time": 23232,

"update_time": null,

"content": {

"content_type": "code",

"language": "unknown",

"response_format_name": null,

"text": "{\"search_query\":[{\"q\":\"https://r.jina.ai/http://https://www.mecagoenlos.com/Posicionamiento/metodos-para-indexar-pginas.php\"}],\"response_length\":\"short\"}"

},

This open https://r.jina.ai/https://www.mecagoenlos.com/Posicionamiento/metodos-para-indexar-pginas.php

In the end, it makes an HTTP request to Jina service https://r.jina.ai/https://www.mecagoenlos.com/Posicionamiento/metodos-para-indexar-pginas.php and returns the content in Markdown format.

Could it be a tool enabled by OpenAI, or did the bot figure it out on its own?

I like to placate it too